When is a fish not a fish? When it’s a starfish!

These crafty members of the Echinoderm family fascinate everyone – from the general public to the most advanced aquarist. And since they come in every color, pattern, and (yes) even shape, it’s no wonder.

There are over 2,000 species in the Asteroidea family. This includes everything from sea stars brittle stars (Ophiuroidea) to feather stars (Crinoidea).

All of the members share radial symmetry and tube feet. How things get arranged from there varies, though.

Radial symmetry refers to arms that grow around a single point. And it isn’t unique to starfish. All echinoderms share radial symmetry (yup, even sea cucumbers).

Most starfish have the expected five arms, but some species go up to FORTY.

Then you have the tube feet. These little adaptations pop up in ALL of the echinoderms. But sea stars put them to the most use.

You can find up to 15,000 tube feet at work on these beauties, working to move these saltwater invertebrates across reefs around the world.

With such cool features, who wouldn’t want to add one to their reef tank?

Unfortunately, starfish aren’t the easiest creatures to manage. Depending on the species, you can run into trouble with management. So before you decide to bring one (or more) home, know what you’re in for.

In this article

Echinoderm Adaptations

Echinoderms may just make up more biomass on the planet than anyone else (if you skip single-celled organisms). There are THAT many!

They inhabit every part of the ocean, from rocky shallows to the deepest abyss. And that means exploiting every temperature range.

You don’t get that kind of global “domination” without developing some essential adaptations.

You won’t find any two families looking alike (despite their common characteristics). But starfish have some unique adaptations that have helped them in their oceanwide expansion.

Starfish Skin

Sea stars sport an external “shell” made up of papulae. The papulae often resemble tough outer casings, and they DO convey protection for the invertebrate – to some extent.

However, they’re thinner than most people think. Throughout the papulae are dermal gills.

The gills connect directly to the starfish’s coelom (central body cavity), allowing for proper gas exchange. Essentially, that shell enables the starfish to breathe as they move through the water. Sounds cool, right?

Unfortunately, it also creates problems. People LOVE picking up and touching sea stars. Do a quick search on social media, and you’ll find millions of pictures. What you WON’T see is the impact on the poor starfish.

Those papulae end up clogged with the oils from our skin. This leads to an immediate reduction in their capability to breathe.

And while they DO have clever tube feet, they can’t scrub the oils (or lotion or whatever was on your hands) OFF.

Not to mention you have bacteria that live on your skin. (It’s natural and healthy) Starfish don’t have an immunity to those bacteria. The thin shell can’t defend against the invasion. Now they’re stuck battling an unwanted infection – one NOT native to the ocean.

You should NEVER handle a sea star with your bare hands. It could result in the echinoderm’s death.

Always wear gloves if you need to pick up a starfish from your saltwater aquarium. It’s the safest way for you to touch them.

Starfish Tube Feet

What moves a sea star around? Tube feet. Through control of hydrostatic pressure, these clever little creatures manipulate their tube feet.

Some of the fastest starfish can move up to three meters a minute (which is pretty fast for the average echinoderm).

The tube feet also participate in gas exchange. It makes them efficient invertebrates. As they move throughout the marine world, they gather oxygen from the surrounding waters. It’s not a bad way of life!

Starfish also use their tube feet when they feed. With thousands of little feet at their disposal, they can leverage mollusk shells open wide enough to get at the yummy center inside. (It sounds impossible, but they only need 0.1mm – that’s not much!)

Starfish and Regeneration

Starfish have long participated in scientific studies regarding regeneration. During periods of intense stress (or when suffering harassment from another species), a sea star can “drop” an arm.

Provided the environment is entirely healthy (something novice aquarists need to keep in mind), the arm will regenerate over time.

This is what happens when you see asymmetrical limbs. The starfish in question lost an arm and is in the process of regrowth.

Some species are more prone to this habit than others. Brittle stars (which is where their name comes from) and serpent starfish are the most common species to drop limbs.

Species with thicker bodies are less likely to do so (but it’s not impossible).

Keeping Starfish

During snorkeling and diving trips, people often glimpse sea stars resting on the sand or coral.

They look stunning and peaceful. And the desire to add one to a saltwater aquarium rises. Why not keep one for the beauty?

Unfortunately, starfish aren’t for beginners. When they get inside a reef tank, they often become destructive. Assuming they survive, anyway.

Tey LOOK hardy, but they’re incredibly delicate. And if you don’t have a mature, cycled marine tank, your starfish won’t last.

Sea stars will NOT tolerate sudden changes in water quality. If you see arms fall off, you know you have a severe problem.

You need to test your water conditions right away. And you MUST avoid using anything copper-based. Similar to shrimp, it’s toxic to these invertebrates.

Food and Diet

Before you bring a starfish home, research the species carefully. They have different feeding requirements, and you may need to provide supplemental feedings.

In the wild, you find everything from scavengers to carnivores. The menu is crazy:

- Barnacles

- Clams

- Coral polyps

- Detritus

- Fish

- Hermit crabs

- Mussels

- Oysters

- Plankton

- Sea snails

- Sea urchins

- Seaweed

- Snails

- Starfish.

True, no starfish eats ALL of these things. That’s why you need to do your homework.

You may need to keep a ready supply of meaty substitutes, such as shrimp. Or you may need to restock your live sand EVERY DAY. You may also need to hide your coral.

Starfish have two stomachs. The cardiac stomach (so named as it’s closest to their heart) protrudes through their mouth. This is how they digest clams, mussels, and oysters.

As soon as they have an opening, the cardiac stomach slides in and dissolves the meaty interior.

Once the cardiac stomach finishes, they withdraw the stomach, and the pyloric stomach goes to work. The remainder of the digestion process happens there (internally).

This two-stage process allows these invertebrates to eat food MUCH larger than them – yes, even fish.

Types of Starfish

People have loved starfish since ancient times. The varied colors and patterns intrigue everyone.

But bringing one home and adding it to your reef tank can get tricky. These saltwater invertebrates come from EVERYWHERE, in every kind of condition. They may not suit.

Always do your homework. Make sure the species you want won’t destroy your carefully-built reef tank.

Consider the temperature of their native region. Look how LARGE the sea star is likely to get. And think about the preferred diet and whether you can accommodate those needs.

Before you bring a starfish home, look at the echinoderm carefully. You shouldn’t see a limp sea star. You also don’t want to see any wounds.

An open gap in the shell is an invitation for bacteria and infection. Skip that starfish and choose another.

1. Amur Starfish/Northern Pacific Sea Star (Asteias amurensis)

- In the Wild: Pacific

- Length: 20 inches (51 cm)

- Reef-Safe? No

- Difficulty: N/A

- Temperament: Peaceful

- Tank Size: N/A

- Diet: Carnivore

- Cost: N/A

Amur starfish hold the dubious honor of appearing on the Global Invasive Species Database of the 100 WORST Invasive Species.

Also known as the Northern Pacific sea star, these orange to purple starfish have made their (unwanted) presence known throughout the Pacific.

Initially, Amurs started near Japan and Russia. They then ended up introduced as far south as Tasmania and even across the Pacific into Alaska AND over into Maine.

They happily tolerate all ranges of salinity, from the coast and up into estuaries.

You WON’T find these pests collected for aquariums. In fact, fishing industries organize “sea star hunting” days to REMOVE Amurs from coasts.

They’ve made horrible economic impacts throughout the Pacific. Not a starfish to covet.

2. Brittle Star (Class: Ophiuroidea)

- In the Wild: Worldwide

- Length: Up to 12 inches (30.5 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Easy

- Temperament: Mostly Peaceful

- Tank Size: 20 Gallons (75 l)

- Diet: Detritivore

- Cost: $15

Brittle stars look distinct from other sea stars. Their fragile (and easily broken) arms behave similarly to lizard tails.

When threatened, the arm continues to move to distract a predator. Meanwhile, the brittle star uses its tube feet to escape.

The majority of brittle stars scavenge the tank, making ideal additions to the clean-up crew. Additional feedings with brine shrimp or Tubifex worms are appreciated, though.

You may even end up with one accidentally when you purchase live rock for your reef tank.

Green brittle stars (Ophiarachna incrassata) are exceptions to the rule. These larger members of the group go after the shrimp and fish in your tank.

They don’t have the most substantial grip in the world (they’re still “brittle”), but they’re an annoyance all the same.

3. Chocolate Chip Starfish (Protoreaster nodosus)

- In the Wild: Indo-Pacific

- Length: Up to 15 inches (38 cm)

- Reef-Safe? No

- Difficulty: Easy

- Temperament: Semi-Aggressive

- Tank Size: 30 Gallons (113 l)

- Diet: Carnivore

- Cost: $10

Once you see a chocolate chip starfish, you know exactly how they got their name. They have prominent spines in a dark color that stands out against their white-orange shell.

One of the most active sea stars out there, they’re a favorite beginner species.

Unfortunately, they’re NOT reef-safe. With a voracious appetite (one of the things that keeps them moving), they’ll destroy your SPS or LPS corals, anemones, and shellfish within days.

It’s cool watching them eat the fish you put near them, but NOT cool watching your coral disappear.

And while they ARE easy to keep, they still have that starfish sensitivity. You can’t slack off on your water quality.

You’ll want to make sure you keep everything as stable as possible to prevent them from getting stressed.

4. Common Comet Starfish (Linckia guildingi)

- In the Wild: Atlantic

- Length: 16 inches (40.6 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Moderate

- Temperament: Peaceful

- Tank Size: 100 Gallons (378 l)

- Diet: Omnivore

- Cost: $20-$30

The comet starfish gets its name from the uneven length of its arms.

You’ll see anywhere from four to seven arms, and they range in size, producing a comet shape. Unlike other sea stars, this ISN’T from dropped arms and regrowth – it’s a standard for the species.

The shape results from the asexual reproduction the species goes through.

The longest arm comes from the parent starfish. The others then result from normal regeneration. It’s a pretty cool little invertebrate!

Comets start in the gray to purple range of colors. Now and then, you’ll see red. As they get older, they usually turn gray.

It IS possible to see some reds and tans pop up, though it’s not as common.

5. Feather Stars (Class: Crinoidea)

- In the Wild: Worldwide

- Length: Up to 12 inches (30.5 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Difficult

- Temperament: Peaceful

- Tank Size: 100 Gallons (378 l)

- Diet: Omnivore

- Cost: $80

Feather stars also show up listed as sea lilies. And it’s no wonder – they resemble free-floating flowers more than they do sea stars.

They’re an ancient group in the starfish family. And if you want to add one to your marine tank, you need TONS of experience.

Feather stars are suspension feeders. They filter microscopic plankton out of the water column.

For YOU to duplicate that, you need pristine water conditions, protein skimmers, and a CONSTANT stream of food.

Even with the best marine setups, most feather stars shed their arms one at a time, lose their color, and die.

They are ALWAYS wild-caught, which means you’ll also need to cope with hitchhikers entering your tank when the feathers pass away.

6. Fromia Starfish (Fromia spp.)

- In the Wild: Worldwide

- Length: 3-4 inches (7-10 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Difficult

- Temperament: Semi-Aggressive

- Tank Size: 30 Gallons (113 l)

- Diet: Specialists

- Cost: $25-$35

You find many Fromia starfish within the genus, and the majority are all reef-safe.

They come in the expected sea star shape, and you find plenty of colors to brighten your aquarium. One of the most popular is the black-tip fromia (Fromia milleporella).

Unfortunately, fromias aren’t the easiest of starfish to handle.

You usually only get to keep ONE per tank unless you upgrade your space to provide a massive territory. They simply don’t get along with one another.

Even worse, the genus features many specialist diets. Some only feed on microalgae. Others only want to eat encrusting sponges.

You’ll need to do your homework on your particular species and make sure you can satisfy their specific menu.

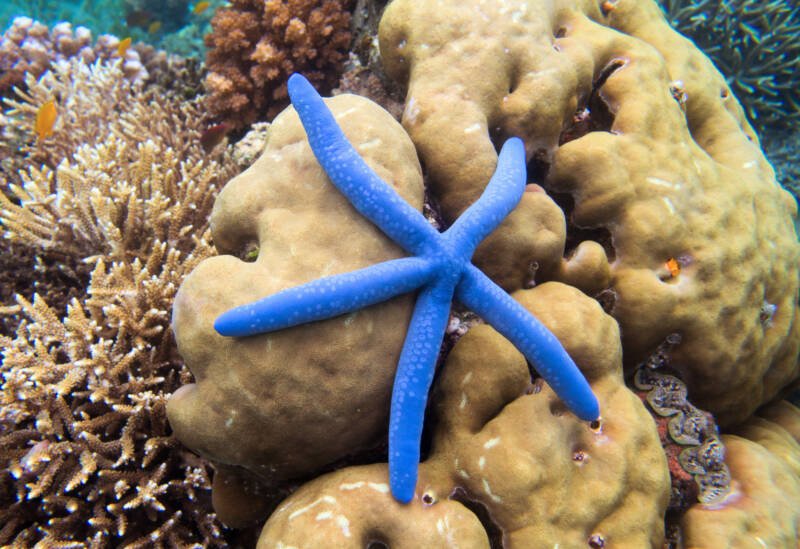

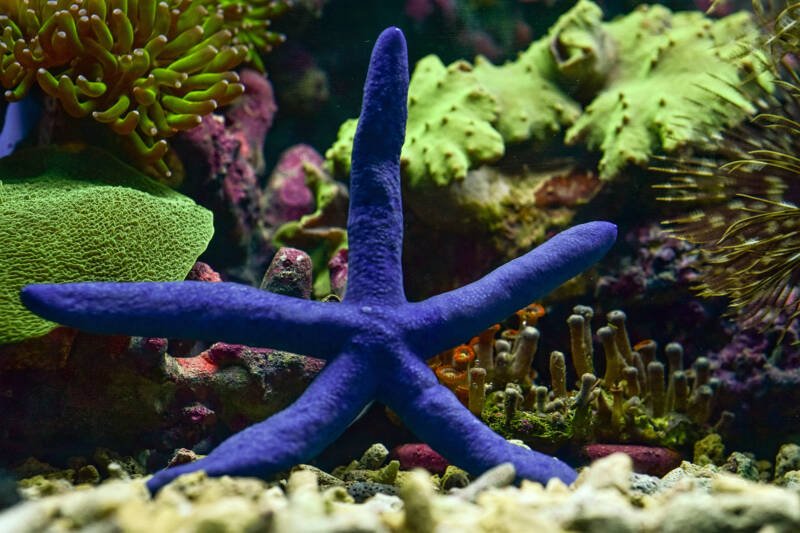

7. Linckia Starfish (Linckia laevigata)

- In the Wild: Indo-Pacific

- Length: 12 inches (30.5 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Difficult

- Temperament: Peaceful

- Tank Size: 50 Gallons (189 l)

- Diet: Detritivore

- Cost: $20-$50

If you’re looking for a striking member of the sea star family, the Linckia starfish fits the bill, especially the blue Linckia.

Unfortunately, they’re one of the WORST starfish for novice aquarists to consider.

When it comes to stress, blue Linckias are the poster invertebrates. Gorgeous cobalt on the reef, by the time they hit fish stores, they’re faded and turning WHITE. It’s a sign of disaster on the way. Many have parasitic snails and infections.

If you DO find a healthy Linckia, you need to supply them with a healthy coral system.

They feed on detritus and algae. That means plenty of live rock they can skim throughout the day. Without a proper supply of food, they get stressed all over again.

8. Luzon Starfish (Echinaster luzonicus)

- In the Wild: Indo-Pacific

- Length: 5 inches (13 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Easy

- Temperament: Peaceful

- Tank Size: 30 Gallons (113 l)

- Diet: Detritivore

- Cost: $30-$60

Similar to the comet starfish, Luzon starfish reproduce through asexual reproduction.

You won’t get that comet shape, but it’s always an interesting fact. (Echinoderms, in general, have interesting reproduction techniques)

Luzons play host to several other organisms. In the wild, you’ll sometimes notice parasitic limpets, as well as comb jellies and commensal copepods. They aren’t common in Luzons in fish stores, though.

Like other starfish that feed on the detritivore side of the menu, you want to make sure you have plenty of live rock and algae.

Luzons are perfect additions to your clean-up crew. They scrape down the biofilm alongside your cleaner shrimp.

9. Marble Starfish (Fromia elegans)

- In the Wild: Indo-Pacific

- Length: 6 inches (15 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Moderate

- Temperament: Semi-Aggressive

- Tank Size: 30 Gallons (113 l)

- Diet: Omnivore

- Cost: $35-$60

You can find marble starfish as the label on potentially any Fromia starfish. However, usually, people refer to the Fromia elegans species.

They’re slightly larger than other Fromias, but they retain the same sea star look and come in assorted colors.

Overall, they sample all of the leftovers in your tank. You’ll want to make sure you allow for sufficient algae and biofilm growth to keep your marble happy.

However, you CAN offer meat supplements in the form of fish or shrimp puree, and they’ll accept it.

While more flexible than other starfish species, marble starfish still won’t tolerate sudden changes in water conditions.

They have a hardier appearance than some of the more delicate designs out there, but they can still succumb to stress.

10. Red-Knobbed Starfish (Protoreaster link)

- In the Wild: Indo-Pacific

- Length: Up to 12 inches (30.5 cm)

- Reef-Safe? No

- Difficulty: Easy

- Temperament: Semi-Aggressive

- Tank Size: 55 Gallons (208 l)

- Diet: Carnivore

- Cost: $60

Red-knobbed starfish share the same prominent spines as the chocolate chip starfish.

Red-knobbeds just don’t have the dark spots. Instead, you see a bright red color on a softer background. They two look similar, and they share the same genus.

They also share the same appetite for destruction. Red-knobbed starfish will take out soft polyp stone (SPS) corals, shrimp, anemones, and shellfish without a second thought.

You should NEVER add them to a reef tank (unless you WANT complete devastation).

The sharp spines and a natural chemical defense system allow them to hold their own against predators, though. So if you’d like to incorporate them into a fish-only saltwater aquarium, you can do so without a problem.

11. Sand-Sifting Starfish (Astropecten polyacanthus)

- In the Wild: Indo-Pacific

- Length: 8 inches (20 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Easy

- Temperament: Peaceful

- Tank Size: 10 Gallons (38 l)

- Diet: Detritivore

- Cost: $20-$40

Aquarists love sand-sifting starfish. Why?

Through their natural habits of filtering sand, they overturn the substrate. It’s a healthy clean-up process that removes trapped particles of decomposing waste from the bottom.

Unhappily, these little sea stars also disturb ALL of the sand in your marine tank. And once they remove all of the waste, you need to replace it. They have to eat, after all.

And if they don’t have food, they’ll bury themselves in the sand to die. Then you’ll REALLY have a problem.

As long as you stay on top of their dietary needs, though, sand-sifting starfish aren’t challenging to manage. They won’t hassle your reef residents (they actually help them out).

And they don’t get particularly large. It makes them a suitable species for beginners.

12. Serpent Starfish (Ophioderma spp.)

- In the Wild: Worldwide

- Length: Up to 12 inches (30.5 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Easy

- Temperament: Peaceful

- Tank Size: 50 Gallons (189 l)

- Diet: Omnivore

- Cost: $30

If you take a brittle star and remove the “spikes” from the arms’ ends, you get a serpent starfish.

They come from the same class, and they share the same habit of dropping their arms during an encounter with a predator.

Serpent starfish venture out into the tank during the evening hours to scavenge for food.

They’ll eat just about anything they encounter. And since they don’t bother anyone else, they’re perfect for reef tank setups.

You still need to take special care of those “brittle” arms, though. They’re not as hardy as other sea star species.

So if you have aggressive fish species in your marine tank, consider skipping this echinoderm.

13. Tile Starfish (Fromia monilis)

- In the Wild: Indo-Pacific

- Length: 6 inches (15 cm)

- Reef-Safe? Yes

- Difficulty: Moderate

- Temperament: Semi-Aggressive

- Tank Size: 50 Gallons (151 l)

- Diet: Omnivore

- Cost: $30-$40

You’ll often see tile and marble starfish used as interchangeable names.

Tiles are a little more common, with a central disc of orange to red, spreading out to lighter shades on the arms. As you might expect, you get that star pattern of five symmetrical arms.

Realistically, the entire Fromia genus works under the same conditions. They scour the surface within a saltwater aquarium, looking for healthy algae colonies. They’ll also feed on leftovers in the tank.

If you double the size of your marine aquarium, you can consider pairing up two tile starfish.

It’s the only way they’ll accept sharing space with their species. (And that goes for the entire Fromia group)

From Sky to Sea

Aquarists have longed to add starfish to their aquariums since they first caught sight of these multi-armed wonders.

While not always as active as other members of the aquatic realm, they’re still fascinating to watch.

But starfish and aquariums are often a challenge. You have to balance their delicate nature with a demanding (and voracious) appetite.

And not every sea star plays nicely in reef tanks. If you’re not careful about your research, you can end up with a disaster.

When everything comes together seamlessly, though, the results are as spectacular as the night sky. You get a gorgeous saltwater aquarium, complete with fish, corals, anemones, AND sea stars. And everyone works together in harmony.

Do you keep starfish? What’s the worst problem you’ve encountered regarding care?

Has a sea star ever dropped an arm on you?

Share your stories and questions with us here!